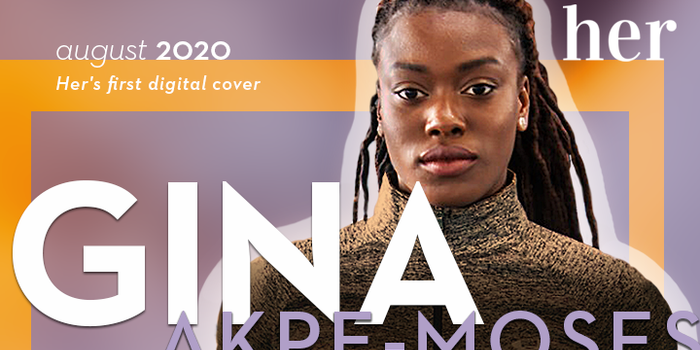

You’re reading Her’s first digital cover story. August 2020’s star is Ireland’s own athlete and track star, Gina Akpe-Moses.

“You’re gonna fail more than you’re gonna win.”

Gina Akpe-Moses doesn’t want to be known as the best of the best yet. That, she says, is still to come.

Ireland’s track star has got the Olympics on her mind and she’s determined to do whatever it takes to get there. But until that day, the 21-year-old is adamant that she’s still got a lot of work to do.

“How do I word this so I don’t sound like I’m being too hard on myself?” she asks.

“It’s nice that people can see the potential in me and recognise my hard work. It’s not that I don’t want to be the best of the best – but that in due time I will be.”

In 2017, Gina won gold at the European Under-20s championships in Grosetto, the first Irish woman ever to win a sprint gold medal at junior level.

Gina had gone into the competition not expecting much. And she had won it.

“It’s all a bit of a blur,” she says. “I knew when I crossed the line that I won, my reaction said it all.

“I didn’t expect it in the slightest. I came into the competition basically injured. Earlier that year I wasn’t able to run, I was barely able to walk at one point. To go from that to getting a gold was a big achievement. It was a big deal.”

Gina realised she was exceptional at track the same way most people discover a hidden talent: by complete accident.

Growing up in Dundalk, she used to race the boys in school, quickly realising that she was faster than all of them. When her sister started running sessions in the green near their home, Gina decided to tag along.

Inspirations and idols came later, she says. In the beginning, she only had herself to focus on.

“I was eight-years-old,” she says. “I wasn’t really looking at anyone else thinking ‘I really want to be like this person.’

“I did it because I had fun. I didn’t really have anyone I looked up to, it was just me, and I was always trying to be a better version of myself.”

Born in Lagos to Nigerian parents, moving to Ireland at the age of three, and eventually relocating to Birmingham to join an elite track club, Gina’s identity spans several nations.

Countless times she has represented her country and done Ireland proud. But unfortunately for some, pride only means so much when you don’t look like the other women in the squad.

“Why is there a black girl on the Irish team?” she recounted in an interview earlier this year, detailing the often subtle yet still prevalent racism experienced while running for her country.

The bulk of racial abuse Gina has been subjected to has, unsurprisingly, happened online. One particular instance involved the accidental sharing of a backwards Irish flag on Twitter while celebrating a win.

Cue the “she’s not really Irish, though” brigade, waiting and ready to jump at the opportunity to diminish a young woman’s achievement, simply because of the colour of her skin.

“It’s easier to attack somebody when you can’t see them,” says Gina. “You know keyboard warriors, a lot of the time people who talk behind your back will never say it to your face because they know the repercussions. They haven’t got the confidence to actually speak to you like that.

“I don’t let myself get bothered by it because you know what? If they saw me in real life they would not say anything to me. They’d be like, ‘Oh my god, you’re amazing.’ They’d be congratulating me.”

Following the death of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter protests that followed, Gina was one of many who spoke up.

Racial abuse was not something she was overtly aware of growing up in Dundalk. Rather as she got older, she realised that discrimination was more subtle in Ireland – and in the athletics world too.

“There’s that stereotype of, ‘Oh, you’re black, you have to be good,'” she says.

“You’re expected to be this fast, you’re expected to win every single thing. It’s hard, because when you make a little mistake, or you don’t achieve a certain goal, it’s like, ‘Oh but you’re black, why didn’t you?’

“It is a bit of a burden, that pressure. But I feel like I can’t focus on that too much, I have to say to myself: I am human. I will make mistakes. If I let that weigh too heavy on me, I’m not going to get very far.”

Holding your own can often come with its challenges, says Gina, whether in the sporting world or online in general.

She has experienced her share of targeted hate on social media. Some because she’s a woman, some because she’s a black woman – and none that she lets get to her.

“People will always have something negative to say, whether it’s racial abuse or whether it’s about being a female in general,” she says.

“We go through enough adversity being women. Being black only adds to it [but] I can’t let my emotions get in the way. You shouldn’t let other people’s words and external experiences affect you too much. You have to remind yourself of that constantly or else you will drive yourself insane.”

Gina is not willing to dwell on the criticism that she might receive herself, but she is concerned by the damaging and oftentimes unchecked systemic racism that continues to permeate society.

June’s #BlackoutTuesday saw Instagram populated by images of black squares. What started as a movement specific to the music industry quickly became a global phenomenon, as millions of accounts began engaging with the cause.

The campaign was somewhat diluted by the sharing of plain black tiles containing little to no information, but elsewhere discussions were occurring, resources were being shared, and necessary education was happening.

On Instagram, Gina posted a freedom fist featuring the names of the black men and women who had been killed by police overseas. On Twitter, she called on those who have a platform to use it.

She didn’t feel like she had a responsibility to speak up – but that she had finally been given the chance to.

“Let’s be honest, when people usually speak out about race, they get scorned for it,” she says. “They get told: it’s not a race issue.

“With Black Lives Matter, you get to hop on and support it. I felt I could speak more freely because a lot of the time you see people stand up and it’s like ‘Oh, here we go again.’

“This movement did help a lot of people, not come out of their shell, but to let it all out. It was like having a scratch and finally getting to itch it.”

Now as we enter August, much of the coverage around Black Lives Matter has waned, but Gina is hopeful that the scale of the protests, as well as the vocal and warranted frustrations of the black community, will be enough to incite real change.

“This has been an awakening for black people,” she says, “a chance for us to get more education out there.

“We need more black people as teachers, more black people as lawyers, more black people as doctors. It’s an opportunity for us to spread ourselves out more, and to make the environment safer for everyone.”

Gina points to the healthcare system as an example of an environment that is currently not safe.

The insidious discrimination of black people means that black women are four times more likely to die in childbirth compared to their white counterparts. This is because of socioeconomic differences and a lack of access to appropriate care, but also because black women are often not listened to.

“Our pain is misjudged,” says Gina. “Doctors say ‘Oh she’s not really in that much pain,’ they ignore what we feel and what we experience and that’s racial discrimination.

“We need people who are kind and supportive. We need to know we’re being taken care of.

“30 years down the line, I don’t want to hear that we’re still fighting for the same thing. There needs to be change.”